Armchair Oscars – 1979

Best Picture

THE WINNER:

Kramer vs. Kramer (Directed by Robert Benton)

The Nominees: All the Jazz, Apocalypse Now, Breaking Away, Norma Rae

MY CHOICE:

Manhattan (Directed by Woody Allen)

My Nominees: Apocalypse Now (Francis Ford Coppola), Alien (Ridley Scott), Being There (Hal Ashby), The Black Stallion (Caroll Ballard), The China Syndrome (James Bridges), Norma Rae (Martin Ritt), The Onion Field (Harold Becker), Saint Jack (Peter Bogdanovich), 10 (Blake Edwards)

For years I didn’t like Woody Allen’s Manhattan. I first saw it as a teenager and at that time it became part of my dislike for the more artistic, more serious Allen that had begun with Annie Hall. Gone were the days of his slapstick gems like Bananas, Sleeper, Love and Death and Take the Money and Run and it wasn’t until my adulthood that I began to appreciate Woody’s golden era, the time when he gave us Radio Days, Hannah and her Sisters, Crimes and Misdemeanors and the film that would become my favorite of his works, Manhattan.

The film was part of a remarkable closing year for the decade. Nineteen Seventy-Nine was a year that saw more great films than any single year of the decade to come. Yet the academy’s selection was a film I found unremarkable, Robert Benton’s Kramer vs. Kramer, a melodrama about a work-obsessed family man whose wife walks out because of his inattention leaving him to raise an eight year-old son that he hardly knows.

With the divorce rate at an all-time high, the academy must have felt itself proud to have rewarded such an expose on the “Me Decade”, but with that logic, I can’t understand why Manhattan didn’t receive even a nomination as Best Picture. The academy, feeling that it had rewarded the new Woody two years earlier with Annie Hall were not so eager to give him credit (though he received a nomination for co-writing the script). That would have probably suited the director just fine, he hated the film so much that he told United Artists that he would make his next film for free if they would shelve this one. I’m glad they didn’t listen, this may be Allen’s least favorite of his directorial efforts but for me, it is my favorite.

Manhattan is the greatest love poem to a cinema artist’s native land since Fellini’s Roma. Allen presents Manhattan with a rapturous passion opening with loving shots of Broadway, 42nd Street, The Brooklyn Bridge, Times Square and of course his famous shot of the New York skyline at sunset looking west across Central Park. There’s something magical about these scenes which are accompanied by George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” as the sun sets and night falls over Manhattan culminating in a beautiful fireworks display. I love that he interposes the voice of his character Isaac who is trying unsuccessfully to describe his feelings for his favorite city. He tries, over and over to find the words but they fail him until he arrives at a description that we feel that he will probably change later.

The irony is that Isaac can’t seem to get his love life in order, he loves the city in which he dwells but can’t find a human relationship that is just as meaningful. He is furious at his ex-wife (Meryl Streep) who has sparked the interest of a publisher after she wrote a book about the deterioration of their marriage and how she left him for another woman (there’s also talk of a movie deal). Meanwhile, he tries to be understanding while his best friend Yale (Michael Murphy) has an extramarital affair with Mary (Diane Keaton), an intellectual snob who hates everything yet never seems to have a series of organized thoughts in her head. Compounded on top of these issues is that fact that 42 year-old Isaac is dating 17 year-old Tracy (Mariel Hemingway), he has fun with her, knows that the relationship can’t go anywhere but won’t end it before Tracy gets too attached.

Isaac is not lovable, he is immature, stuck somewhere between adolescent cynicism and intellectual pessimism. He is a successful writer on a hit television show but he hates the show and leaves it in a huff, intending to write his novel (everyone in this movie seems to be writing a book). He has a radical change in lifestyle as leaving the show means a smaller apartment with a noisy upstairs neighbor and pipes that dispense brown water. Tracy is still in love with him but he reminds her (and probably himself) that their affair is only temporary until she goes to school in London and further to a bright future.

When Yale goes back to his wife, he suggests that Isaac and Mary should get together. During a conversation one night while walking through Manhattan, he listens and talks with Mary and slowly realizes that – despite his initial distaste – he kind of likes her. There is an otherworldliness to their relationship, Isaac has no real reason to like Mary other than some deeply buried human connection. The most beautiful sequence has the two walking through a planetarium full of light and dark and they move into the shadows and out of the bright lights. There is a shot of the two of them face to face that seems inorganic to the rest of the film.

There is a deeply buried insecurity to the characters in Manhattan, they hide behind a mask of intellectualism but they can’t seem to express themselves or perhaps they are afraid to. They are mired in cynicism, the fear of being alone and the fear of being hurt or maybe just the fear of expressing real emotions, of given your whole heart to someone and having the fear that they will never get it back. Isaac, especially in his relationship with Tracy thinks this because he is the adult that he knows what’s best. There is a heartbreaking scene in which he breaks up with her at a soda fountain, telling her “I’m in love with someone else”. I am stunned by the pain on Tracy’s face, It isn’t bold, but just enough. She has the truest line in the film when she tells him “Now, I don’t feel so good”.

What he doesn’t understand is that his relationship with Tracy is the first meaningful union he has ever experienced, he’s just too blind to realize it. The best scenes in the film take place in the end when he confides that “I think I made a mistake with Tracy”. There is a scene where he lays on his couch telling his tape recorder about “Things that make life worth living” and among Willie Mays, Groucho Marx, Louie Armstrong and the Potatohead Blues, the words “Tracy’s face” bring him to a dead halt and a heartbroken smile.

I think Tracy is the fulcrum. She seems to exist within the same space as these older characters but there is something so unblemished about her, something so truthful. She wears her heart on her sleeve, she is unaffected and says what she means. It is assumed by Isaac that age has given him an advantage but what he misses is that while he may have experience with marriage and love affairs, she has a clearer mind and a heart that is completely unguarded. What is challenging about this relationship is that we disapprove of their union because of their age difference but we have to admit, as Isaac does, that she is perfect for him.

Best Actor

THE WINNER:

Dustin Hoffman (Kramer vs. Kramer)

The Nominees: Jack Lemon (The China Syndrome), Al Pacino (. . . and Justice For All), Roy Scheider (All the Jazz), Peter Sellers (Being There)

MY CHOICE:

Peter Sellers (Being There)

My Nominees: Woody Allen (Manhattan), Ben Gazzara (Saint Jack), Dudley Moore (10), Nick Nolte (North Dallas Forty), Richard Pryor (Richard Pryor Live in Concert), Kelly Reno (The Black Stallion), Martin Sheen (Apocalypse Now)

When Dustin Hoffman won the Best Actor award at the 52nd Annual Academy Awards, less focus was on the merits of his performance then on what he would say when he won. He had recently seemed to be following the footsteps of previous Oscar protesters Marlon Brando and George C. Scott when he called the academy awards “garish” and “obscene” and “No better than a beauty pageant” and yet his speech at the podium was not hateful rabble rousing. Instead, he simply and directly expressed that he had a distaste with the idea of having actors compete with one another.

“I’ve been critical of the academy and with good reason”, he said, “I refuse to believe that I beat Jack Lemmon, that I beat Peter Sellers. I refuse to believe that Robert Duvall lost. We are part of an artistic family. And to that artistic family that strives for excellence, none of you have ever lost, and I am proud to share this with you.” It was a very moving moment and I was glad that Hoffman got the chance to silence some of his critics.

I agree with some of his criticisms but I am also forced to acknowledge that the entire idea of Armchair Oscar is built on the very thing that Hoffman was protesting. It is wrong to compare one performance to another and there is an inherent flawed reasoning behind the entire institution of the Academy Awards. How can you compare one actor’s performance to another? Shouldn’t we celebrate great art and not reduce them to a horse race?

In my case, it doesn’t come down to the decision of which performance is better but which performer gave his or her best. In Hoffman’s case, I don’t think that he gave his best performance in Kramer vs. Kramer. There is something to be admired for taking on the role of the very flawed Ted Kramer, an overworked businessman whose wife walks out, leaving him to raise an eight-year old son he hardly knows, but for his best work, I direct your attention to Little Big Man, The Graduate, Midnight Cowboy, Straight Time, Death of a Salesman or Rain Man. It is in those performances that I think Hoffman shows his best range as a performer.

For Peter Sellers, Being There wasn’t an issue of his range but the chance to play a character we had never seen before. Seller’s list of credits proves that he was a great, versatile performer but nothing we had ever seen in his entire career could have prepared us for Chance the gardner. It is always great to see an actor at the top of his game and for Sellers this farewell performance is a pleasure.

He plays Chance, a gardner who has lived all his life within the confines of a townhouse in Washington D.C. We learn next to nothing about his past other than the fact that he has lived his entire life inside the place being raised by an old man whose connection with him is never explained. The only other occupant of the house is Louise (Ruth Attaway), an elderly housekeeper who doesn’t think much of him. Chance lives within a very confined mental space. He is simple-minded and not cluttered with a lot of notions but rather is occupied only with the things he needs to get through his day. He knows where he goes to sleep, where he goes to the bathroom and he knows the fundamentals of his garden. He also has an all-consuming addiction to television, a device that is not only an escape but also his window to the outside world.

Chance is a very curious character, he speaks in a very flat, genial tone (Sellers borrowed it from Stan Laurel) wears a pleasant smile on his face and dresses in nice suits which are hand-me-downs given to him by the old man. When the old man dies and leaves no provisions for Chance, the lawyers inform him that he must vacate immediately. Stepping out into the world for the very first time, wearing a nice suit and carrying and umbrella and an alligator bag he displays the effects of a wealthy man. Yet, he is a stranger in a strange land, walking through a tough D.C. ghetto past burning barrels, wrecked cars, liquor stores and porn theaters he has no idea what he has encountered. I smile at director Hal Ashby’s decision to accompany Chance’s first steps into the world with a funk remix of “Also Sprach Zarathustra”.

He is also unarmed mentally. When he encounters a group of tough street kids he pulls out his remote control and tries to change the channel but is surprised when it doesn’t work. Later he is baffled by the projection television in a store window in which he sees himself. It is at that moment that he is tapped in the leg by a moving limousine. The woman in the back is Mrs. Eve Rand who insists on taking him to a hospital and then decides to take him to her mansion (she is nice to him because she is afraid that, based on his clothes, he will sue her). Giving him a drink and not realizing that this is his first experience with alcohol, she asks his name and during a coughing fit she mistakes Chance the Gardner as Chauncey Gardner, a perfect name for a man who looks the way he does.

He is especially endearing to Eve’s husband Benjamin (Supporting Actor winner Melvyn Douglas) a billionaire who is dying of a blood disease that generally effects younger people. Benjamin is not the stereotypical grouchy old cuss, in fact he is a nice man who seems at peace with his rapidly approaching rendezvous with the hereafter. He takes to this man who speaks with only a limited vocabulary but reading between the lines of what he thinks Chance means, he seems to Ben to be a brilliant man.

That is the central joke of Being There. Chance speaks in very limited parameters. He only says what he knows and only understands what he says. When he speaks, those around him assume that he is talking about something else. They read between the lines as when Chance is questioned by a television news reporter and is asked what newspaper he reads. “I don’t read, I watch TV.” Of course, not knowing that this man cannot read or write, the news reporter picks that up to mean that he prefers television news to what is written in the papers. There is another moment when Ben introduces Chance to the President of the United States (Jack Warden) and at dinner Chance begins blabbering about the details of tending to a garden. The President, not knowing that Chance really is talking about gardening assumes this is a metaphor for the roots of American democracy:

The President: Mr. Gardner, do you agree with Ben, or do you think that we can stimulate growth through temporary incentives?

Chance: As long as the roots are not severed, all is well. And all will be well in the garden.

The President: In the garden.

Chance: Yes. In the garden, growth has it seasons. First comes spring and summer, but then we have fall and winter. And then we get spring and summer again.

The President: Spring and summer.

Chance: Yes.

The President: Then fall and winter.

Chance: Yes.

Benjamin: I think what our insightful young friend is saying is that we welcome the inevitable seasons of nature, but we’re upset by the seasons of our economy.

Chance: Yes! There will be growth in the spring!

Benjamin: Hmm!

Chance: Hmm!

The President: Hmmm. Well, Mr. Gardner, I must admit that is one of the most refreshing and optimistic statements I’ve heard in a very, very long time.

The President: I admire your good, solid sense. That’s precisely what we lack on Capitol Hill.

Soon Chance is meeting not only with the President but with the Russian Ambassador and heads of state and by the end, is being discussed as a presidential candidate.

The greatness of Sellers performance is that he never allows Chance to grow. Except for his circumstances, he remains more or less the same person at the end of the film that was when we first met him. His body remains erect, his speech pattern very pleasant and dull. His clothing, which we later learn dates back the 20s, is perfectly neat. The presence of Chance suggests a person who is more than he really is. Everyone in the film makes assumptions about him based on what he says, how he looks and what he does. It is a brilliant balancing act of misdirection and misunderstanding. He is a blank slate and everyone projects what they want upon him. The movie has a theme on how we perceive things, how we paint symbolism onto things that sometimes don’t merit them.

There is a theme on the fact that nearly all of the white people love and respect him but there is also a strange theme running through Being There dealing with Chance’s connection with African-Americans. We meet Louise, the housekeeper who is shocked that he would rather watch television than grieve for the old man. There’s a potentially offensive moment when he is watching the Bette Davis movie Jezebel during a scene in which a stereotypical black coach driver tips and hat and repeats “Yazzam” and Chance repeats his motion later when he says goodbye to Louise. She seems to have been the only black person he has ever known and he assumes that the functions that she performed for him will be performed by another black woman that he meets on the street (she runs away). He walks through the black section of D.C. and runs into some tough kids who give him a message for someone named Raphael. Later when Chance is tended to by a black doctor, he tries to give him the message. When Chance is meeting with heads of state, Louise later sees him on television and is dismayed that this simpleton is moving up in the world through people who misunderstand him.

Being There can be interpreted in a million different ways but one thing I can never pin down is the film’s final moment. Why exactly does Chance walk on water? It the film suggesting that he is a Christ-like figure. We could assume that the pond is shallow but that illusion is broken when he puts his umbrella into the water all the way up to the handle. Why this shot? What does it mean. I am at a loss for an answer.

Best Actor

THE WINNER:

Sally Field (Norma Rae)

The Nominees: Jill Clayburgh (Starting Over), Jane Fonda (The China Syndrome), Marsha Mason (Chapter Two), Bette Midler (The Rose)

MY CHOICE:

Sally Field (Norma Rae)

My Nominees: Diane Keaton (Manhattan), Diane Lane (A Little Romance), Bette Midler (The Rose)

Sally Field spent the seventies trying to undo the image that she created in the sixties. She spent the previous decade on television in “Gidgit” and then “The Flying Nun” and then in 1976 she silenced her critics who had written her off by giving an incredible performance as Sybil Dorsett, a woman with thirteen multiple personalities in the TV movie Sybil. She was brilliant in that film but Martin Ritt’s Norma Rae would prove that it was no fluke.

She plays Norma Rae Webster, a 31 year old textile worker who is destined to spend her life working in the O.P. Henley textile mill just like everyone else in her small town. She is a widow with two children, one from her late husband who was killed in a bar fight and the other from a one-night stand. Beyond being a good mother and keeping her job there doesn’t seem to be any other ambition. Then she meets Reuben (Ron Leibman), a union organizer who has come to town to help set up a union in her mill.

Management threatens her, they try to sully her name by making light of her revolving series of boyfriends. She is defiant and when they see that she can’t be bullied or humiliated they try promotion. Promoting her to a checker, she loses some respect from her fellow workers who assume that she has sold out. In the meantime, she marries Sonny (Beau Bridges) and he gets angry with her because she isn’t home to clean up the house. He finds that he can’t intimidate her and is forced to take up the household chores. From Reuben and Sonny she gains admirers, from management they can’t decide what to do.

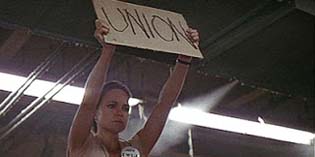

Norma Rae won’t back down, she has no education but she is stubborn, resilient and has a big mouth. The casting of the men is key, they are large, often tall scary looking men and short, skinny Norma stands among them refusing to be intimidated. The film builds through Norma Rae’s struggle so in the end when she copies a memo from the bulletin board in which the mill reminds white workers that blacks will take their jobs if there is a union, she is arrested. That’s when we get her best scene as she is told to leave but refuses to budge, shouting over the roar of the machines “Forget it! I’m stayin’ right where I am. It’s gonna take you and the police department and the fire department and the National Guard to get me outta here!” That’s when she stands on the table, writes “Union” on a pieces of cardboard and holds it over her head. The other workers defiantly turn off their machines and refuse to do anymore work. The film earns the moment, Norma Rae’s struggle has built to that moment so we feel that they understand and that they are protesting because they genuinely feel what she stands for.

Sally Field was perfect to play the part. I don’t feel that I am watching an actor on a set but that she has a presence that makes me believe that she’s been in that mill for years. She is the perfect physical stature as well, she is short and boney but her face is expressive especially when challenged. She is challenged at every turn but she always comes back. When the preacher turns her away from the local church because he won’t allow blacks to attend the meetings, he tells her “We’re going to miss your voice in choir, Norma” and without missing a beat she says “You’re gonna hear it somewhere else”. She has a lower jaw that tightens up when she is angry, moving her lower lip out. Her eyes express everything she is feeling. Norma Rae wears everything she is feeling right on the end of her nose. It is amazing to watch Field come back on those who try to bring her down, we feel her struggle, we feel her pain because Sally Field doesn’t hide anything. She lets Norma Rae’s frustration come through in droves so that we want her to succeed.