A Study in Disney: ‘One Hundred and One Dalmatians’ (1961)

Disney is as much a part of our lives as love and death. It’s wrapped around us, and not just in our childhood. There are thousands and thousands of Disney movies by this point but the one that really shape the company and the culture are the animated features. Disney busted out of the gate in 1937, intending to create a new artform and make an evolutionary leap in cinema. So, every other day from now through March, I will be chronicling every single one of Disney’s canon animated features. It’s a fascinating journey, and a lot of fun too.

One Hundred and One Dalmatians was the first of Walt Disney’s animated features to be released in the 1960s, and with that, it signals a notable change. Only six years out from the lush watercolor grandeur of Lady and the Tramp, here is a movie that embraces a light but not insignificant beat-generation esthetic. Let’s put it this way: if Lady and the Tramp was the equivalent to a symphony for a peaceful Sunday afternoon, then Dalmatians plays more like an evening at a jazz club.

The jazzy and very current approach to the film was born out of financial strategy. In 1959, their previous animated feature Sleeping Beauty became yet another financial casualty due to the work and the cost involved – while not a failure at the box office, it did underperform in a costly way. Gone were the days of large-scale ambitious works of art, realistic characters and backgrounds fit for a museum wall. Instead, Walt and his animators employed a process first brought to him by Ub Iwerks, his Head of Special Processes, a new technique called Xerography.

After World War II, The Xerox Company and its new-fangled copier were suddenly becoming the best friend to the average office worker and, as it turned out, would become the best friend to Disney animators too. The process allowed animators to copy the drawings directly onto the cell alleviating the pains-taking process of hand-drawing and inking each and every cell one by one. That made for a faster process, but artistically, it also meant that the whole palette would have to change. Since the Xerox machine could only copy lines in black, the process eliminated some of the nuances that were the cornerstones of the artistry in Pinocchio and Fantasia and Sleeping Beauty.

And yet, one could argue that having those drawbacks is better than having no Disney at all. Today, it is rather blasphemous to the American mind to consider the idea of the Walt Disney Studios reaching a state in which they are no longer able to produce animated features. Our culture is so married to this studio’s confections that imagining the world without it is like imagining a world that never invented chocolate cake or skateboards or television. Where then is the food for the soul?

The appetite here is provided by a film that is probably the most relaxed animated feature that Walt produced in his lifetime. After the thundering epic of Sleeping Beauty, here is a film of quiet passages, of simple observation. It doesn’t have to thunder us will wall-to-wall music. It is a sweet film for those reasons.

The retooling in artistic process meant alleviating the process of making the characters realistic, a long-held Disney tradition going all the way back to Snow White. As a result, the characters are more stylized and much more consideration is given to shaping the human dimensions. Many of the characters have dog-like dimensions. The two human characters Roger and Anita Radcliff are very human with only very slight dog-like dimensions to their faces (it is small, but the similarity is there). This tiny similarity between father and mother dalmatians Roger and Perdita and their 103 canine companions draws a line between them – a sort of suggestion that the dogs are not much different than those who care for them. Roger and Pongo have the same basic facial structures and so too do Anita and Perdita.

Differing wildly is the film’s chief villain. Cruella is almost a different style of animation. Where Roger, Anita and the dogs have round and inviting edges, Cruella’s physique is very angular perhaps exposing the sharp and dangerous angles of her intentions. She almost seems to come from a different planet then Roger and Anita. Yes, she and Anita went to school together, but why do they put up with her?

The overt comedy of Cruella seems to cut through the horror of her major plot – she wants to skin puppies to make a coat. When you come down through the line of female villains from Disney thus far, Cruella’s intentions are the most horrific since Snow White’s evil witch put in a plot to bury the titular princess alive. Outwardly, of course, Cruella’s machinations are a call against animal cruelty and an anti-fur call that got ahead of the movement of the 1980s by at least 25 years. Previous Disney animated features such as Dumbo, Lady and the Tramp and especially Bambi had dealt with the issue of animal cruelty but never did Walt hide his message and especially not here.

The superfluous nature of Cruella’s machinations makes them even more horrendous. Why is that? Well, it would seem to play hard and fast with the entire nature of the fur industry itself. By the 20th century, animal skins made to be worn had long-since outlasted their usefulness – unlike early explorers who used them as a survival against the harsh environment. In Cruella’s intention, it would seem to be a prestige issue . . . perhaps.

She is an heiress whose stature seems to be that she can have anything she wants at any time, but perhaps there is something more. Her frame (developed by Bill Peet and Ken Andersen and animated by Marc Davis) is very skeletal and so it is interesting that her focal point is on attaining skins for clothing. This bony frame is accented by a large, overflowing white coat that hangs off of her like an animal. Is she trying to regain something? Is she trying to hide something? Why exactly does she need this? The most convenient answer falls back on the issue of vanity.

Cruella is similar to The Evil Queen in Snow White because the machinations of both have to do with vanity, with getting older, with losing something – an issue that men in Disney films never have to deal with. There is a physicality to both characters that has been lost in the adamant of time that has been replaced by a sharp bitterness that leads to desperate measures to get them back. The Evil Queen seeks to dispose of her younger and more beautiful competitor to regain the title of “Fairest in the Land.” Cruella has moved past this. She is one of the only Disney villainesses of these early years that operates without special powers – her only true muscle is her money. In many ways she has moved past her physical looks and now seeks to hide them behind purloined animal skins.

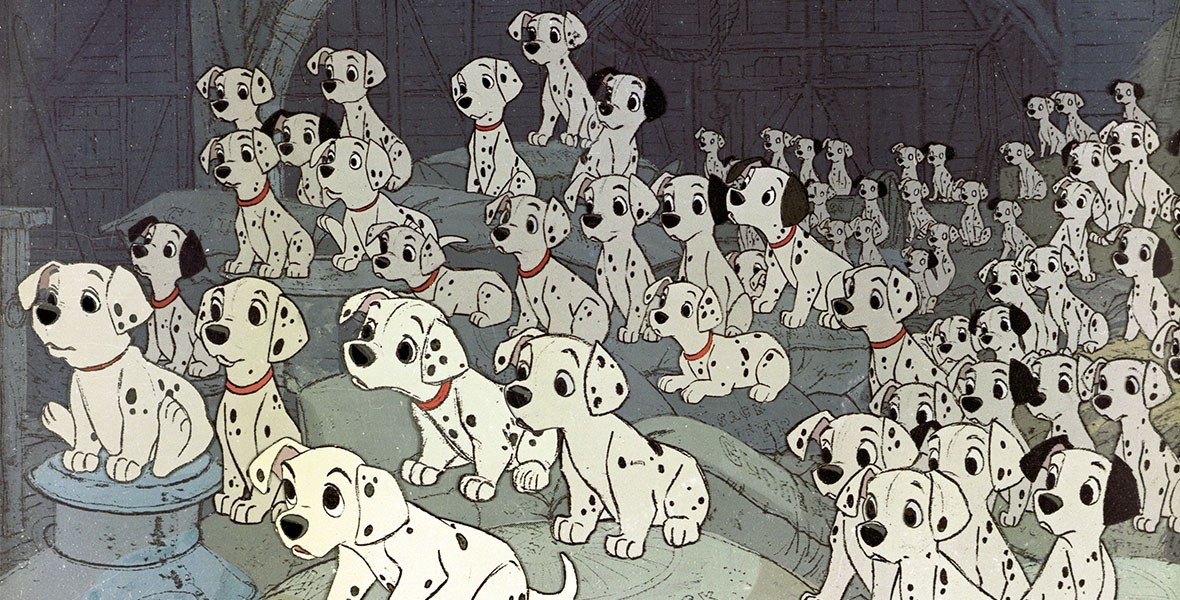

But, of course, that’s all gender politics. The movie’s true source is its cute widdle puppies, and they are adorable even though (reasonably) many don’t have personalities of their own. Rolly, Patch, Penny and Lucky are at the forefront but they don’t seem to have much personality beyond being cute and adorable, and possibly for this film, it is all you really need. Based on the threat that they are under; you don’t need much more than to understand that they are adorable.

One Hundred and One Dalmatians never feels like an artistic statement, more like a grand day out. It feels like a much more laid-back project. There’s nothing really wrong with that, but in assessing the whole scope of Disney’s animated features, you come to realize that this smaller, more cost-effective style of picture is the kind of thing that Disney would turn out for the next three decades. They were financially successful, but you can’t help thinking that during this era the higher, loftier ambitions were put to the side.